By: Susan Sprout

Wild Bergamot

Poking through the recent snow on skinny stems are the spent seed heads of Wild Bergamot.

During the growing season, its two-lipped lavender flowers are held in readiness for blooming by pinkish tubular calyxes. Starting in the center, the flowers bloom outwardly until they form a wreath, then drop off leaving their calyxes. Wild Bergamot, or Monarda fistulosa, is a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae)…square stem and all!

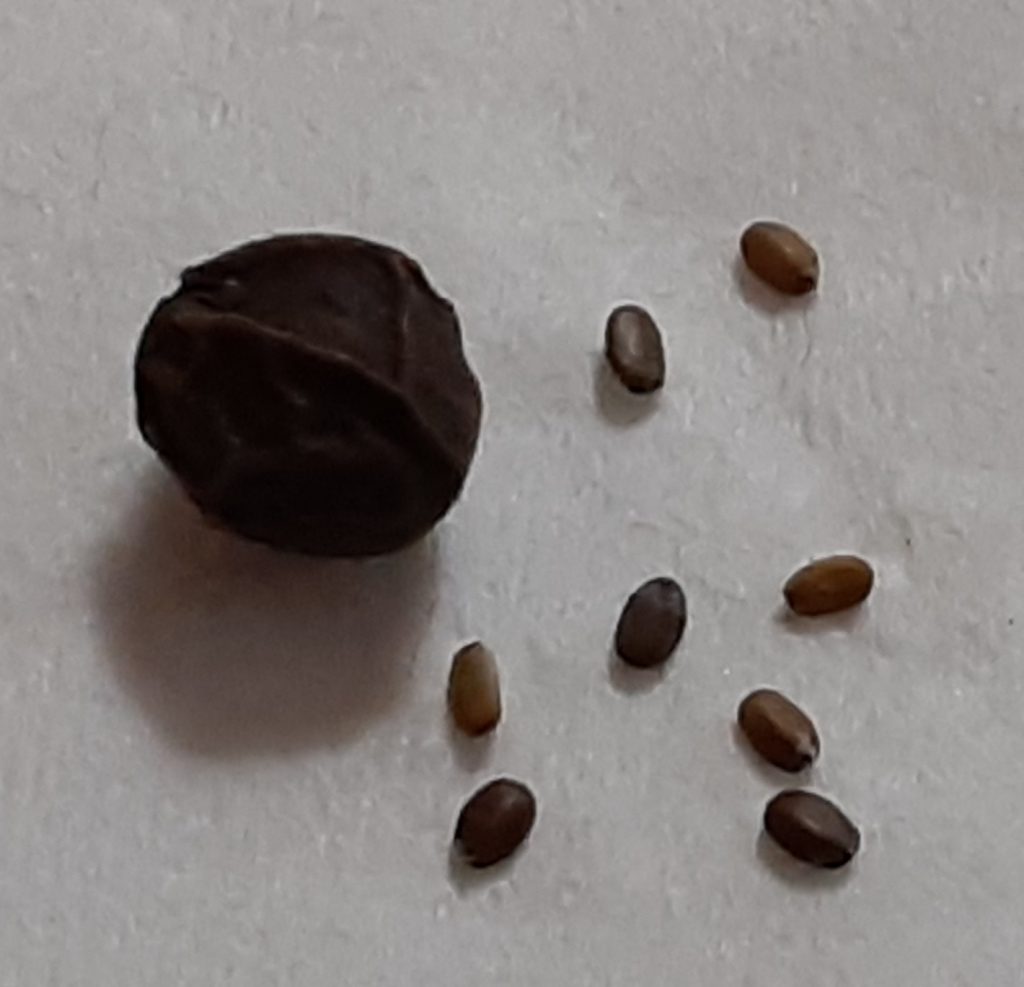

It is a native perennial with several common names that are also used to identify other plants in the same genus. So, we’ll stick with Wild Bergamot. Its species name comes from a Latin word for tube or pipe. Looking at the dried seed head, you can see why! All of the little tubes that held the individual flowers are visible. If you locate the remains of this plant on your rambles or skiing, take a moment to gently stroke the seed heads with your hand underneath them. You may be rewarded with a look at some remaining seeds.

They are tiny, brown, smooth and may take off if its breezy out. Squeeze the seed heads and sniff your fingers to check for any lingering scent. During the bright summer days, so long ago, the whole plant, including its opposite gray-green leaves exuded, a spicy, minty odor which some say resembles oregano, another member of the mint family.

Bald Cypress Tree

An outstanding tree in parks, forests, and yards this time of year is Bald Cypress…because it really does stand out among all the luscious colors of our wintery evergreens. It has lost its leaves, being a deciduous conifer, and appears underdressed!

The stabilizing buttressed trunk looks like thick cords run under its peeling orange and brown bark. Its rather thin branches protrude, creating indents under them like long armpits. O.K. Weird, but that’s how I remember the difference between defoliated Bald Cypress and a defoliated Dawn Redwood which lacks that particular (or peculiar) anthropomorphic body part.

Bald Cypress or Taxodium distichum can grow to 120 feet tall and is a member of the Cupressaceae Family which is found worldwide from Arctic Norway to Southern Chile, except for Antarctica. Its ancient ancestors were living on the supercontinent Pangea when it broke apart about 150 million years ago. Its descended lineages were separated and evolved in isolation from each other creating over 130 different species.

This tree is native to southeastern U.S. and is adaptable to a wide range of soils and amounts of moisture. On stream banks, it can soak up flood waters and prevent erosion. Bald Cypress is the oldest known wetland tree species on earth! For the last fifty years, I have loved looking at and keeping track of the one that is growing about a block away from my house near Muncy Creek.

Find out what’s underfoot with NPC member and environmental educator, Susan Sprout! Catch up on past issues of Underfoot: Introduction & Bloodroot, Trout Lily & Coltsfoot, Blue Cohosh & Dutchman’s Breeches, Ground Ivy & Forget-Me-Nots, Goldthread & Wild Ginger, Common Mullein & Sweet Woodruff, Aniseroot & Butterfly Weed, Myself , Jewelweed & Soapwort, American Pennyroyal & Great Lobelia, Boneset & Common Ragweed, Pokeweed & Blue Chicory, Prickly Cucumber & Wintergreen, Beech Drops & Partridge Berry, Pipsissewa & Nostoc, Witch Hazel, Plantsgiving, Black Jetbead & Decorating with Winterberry.