By Susan Sprout

In the Pennsylvania Wilds, growing in my favorite bog are Cranberries! It may seem odd that I am writing about them “out of season,” since they become mostly red and ready for picking in the fall and for eating at Thanksgiving and Christmas times. Who thinks about fresh cranberries in the spring? I do!

Originally they were known as “craneberries” because the shape of their male reproductive organs, or stamens, tended to resemble a crane’s beak. Wild cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) are native here as well as large areas of Canada and Northeastern United States, southward to Tennessee and North Carolina. Cultivars created from wild species are grown commercially in artificial ponds. The top five states in cranberry production are Massachusetts, New Jersey, Wisconsin, Oregon, and Washington.

Cranberries are members of the Heath Family, Ericaceae, along with locally known plants like huckleberries, teaberries, azaleas, laurels, and rhododendrons which all typically grow in acid soils. Cranberries seem to do well in acid soils in wet, peaty, seepy places – like my favorite bog! I visit there several times a year and have written blogs about five plants found growing in it. Never have I visited in March, until this year…and discovered red berries snuggled down in their brownish-purply, copper winter foliage. I tasted some of the berries left over from last fall and found they do not get any sweeter after freezing like rosehips do. Very tart or sour.

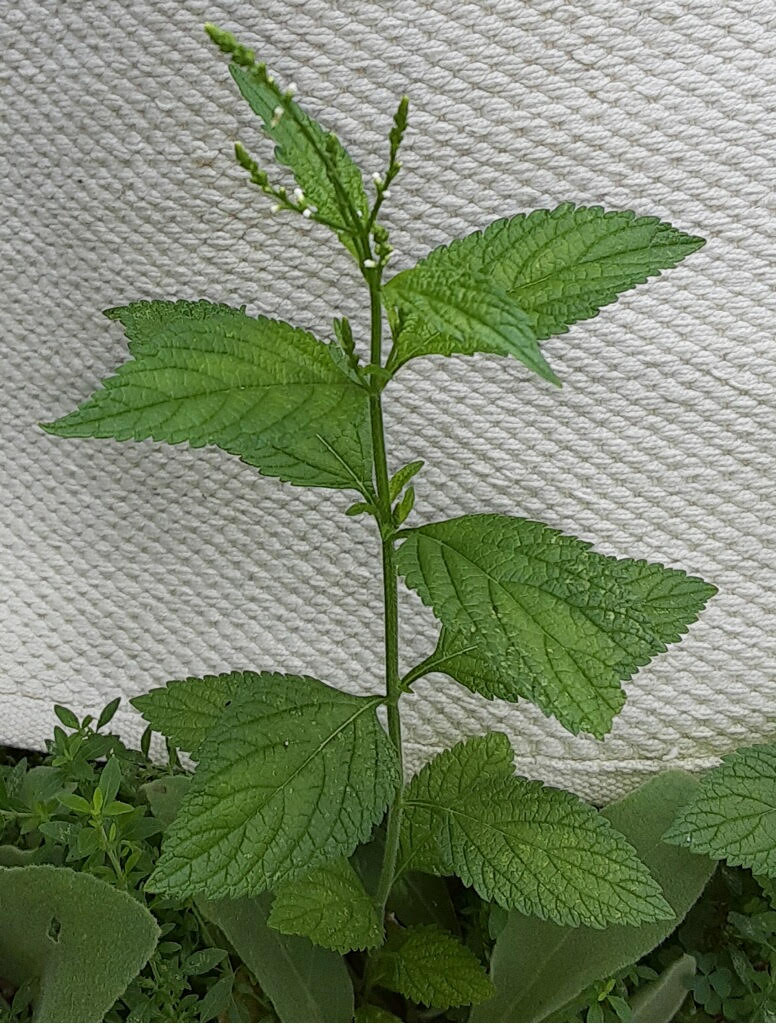

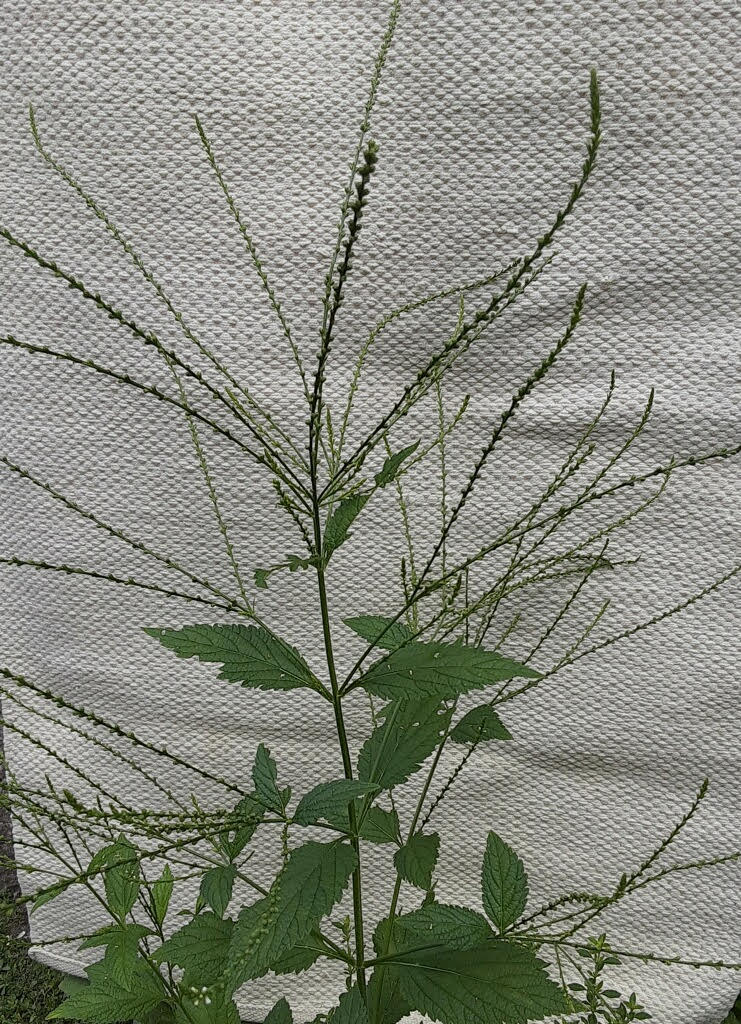

Why did I never notice them growing there before? I think they kind of blended in with the sphagnum mosses and dewberries trailing over the ground there. And they do trail, their wiry stems forming dense masses. Cranberries have small oval leaves growing along stems that spread horizontally for a bit, then curve upward. Their tiny flowers with four backward pointing petals open in late June to form a pinkish-white carpet, ready for pollination by bees, and to create fruit ready for picking in September through November. Also in late summer, new terminal buds begin to form for next year’s crop of berries. They will require a period of dormancy in order to successfully produce flowers and fruit. They must undergo a sufficient period of cold temperatures and short daylight hours called “chill hours” during the winter months in order to break dormancy and open in mid-summer of the next year to start the blooming process all over again. If you count the months, you will see that it takes them from fourteen to sixteen months to produce berries. Hopefully the geographical range where the optimal conditions occur will not shrink due to climate change!

We love our cranberries – rich in Vitamin C and antioxidants! Cranberries, according to NIH National Library of Medicine, can prevent tooth decay, gum disease, inhibit urinary tract infections, reduce inflammation in the body, maintain a healthy digestion system and decrease cholesterol levels. Check out The Cranberry Institute for more information about these powerful little fruits!