Bullfrogs are the largest frog native to  Pennsylvania and are found throughout the state in lakes, ponds and wetlands and along the edge of streams. They are voracious eaters, taking insects, small frogs (even of their own species) and occasionally small ducklings. Bullfrogs are usually varying shades of green in color, although some may be brownish, and have a dorsal fold that begins behind the eye and bends around the tympanum to near the front leg – if the dorsal fold continues along the back to the hind legs the animal is a green frog, a different species. These are the frogs that make the “jug-a-rum” that so many of us have heard as we’ve fished or sat lake-side after dusk. Bullfrog tadpoles may take up to three years to mature and metamorphose into adults. Bullfrogs have been introduced in many areas (western U.S., Europe, Japan and China) where they are not native and have become an invasive exotic species.

Pennsylvania and are found throughout the state in lakes, ponds and wetlands and along the edge of streams. They are voracious eaters, taking insects, small frogs (even of their own species) and occasionally small ducklings. Bullfrogs are usually varying shades of green in color, although some may be brownish, and have a dorsal fold that begins behind the eye and bends around the tympanum to near the front leg – if the dorsal fold continues along the back to the hind legs the animal is a green frog, a different species. These are the frogs that make the “jug-a-rum” that so many of us have heard as we’ve fished or sat lake-side after dusk. Bullfrog tadpoles may take up to three years to mature and metamorphose into adults. Bullfrogs have been introduced in many areas (western U.S., Europe, Japan and China) where they are not native and have become an invasive exotic species.

April 17 is Bat Appreciation Day

Why, you may ask, should you appreciate bats? Lots of reasons. One specific reason is, bats feed on insects. They eat LARGE numbers of insects. This is important especially if you like to eat. Bats eat pests like moths, beetles, flies, true bugs, termites, and flying ants. Many of these pests cause problems with farmers’ crops and even your backyard garden. Bats can help keep the pest numbers in check which allows your fruits and vegetables to grow better.

Why, you may ask, should you appreciate bats? Lots of reasons. One specific reason is, bats feed on insects. They eat LARGE numbers of insects. This is important especially if you like to eat. Bats eat pests like moths, beetles, flies, true bugs, termites, and flying ants. Many of these pests cause problems with farmers’ crops and even your backyard garden. Bats can help keep the pest numbers in check which allows your fruits and vegetables to grow better.

A single little brown bat in Pennsylvania can consume up to 33% of its body weight in insects each night. That’s pretty impressive, but then when you realize that could be up to 3,000 insects a night, it becomes even more impressive.

A lactating female eats even more. She can eat 20% of her body weight in an hour, and over the course of the night, more than 100% of her body weight! That’s a lot of insects!

One of the faculty at Susquehanna University NPC staff interact with studies mammals and provided information for today’s appreciation of bats. Dr. Iudica has spent time studying the little brown bat, Myotis Iucifugus. Its scientific name translates to “the animal with ears like a mouse that flees the light and goes back to its roost at daybreak.”

The little brown bat is a small bat. Typically in the spring, coming out of hibernation it weighs 5 to 10 grams (that’s 0.01 to 0.02 pounds) while in the fall it’s up to 6 to 11 grams. The bat has dark brown dorsal and light-beige ventral fur.

This is one of the most common species of bats. It’s found throughout Pennsylvania. The little brown bat spends its winters hibernating in caves and mines. The winter hibernation site is known as a hibernaculum. Some little brown bats will fly 200 to 300 miles to reach their hibernaculum.

During the summer, the pregnant little brown bat females form large nursery colonies while the males roost alone or in small groups. The summer roost may be between the rafters in a house or a barn. Males will tend to summer roost in more natural places, but still may be found in man-made buildings, just away from the females.

Baby little brown bats are typically born in June. Known as a pup, the baby is ready to fly after 3 weeks.

For more information about little brown bats visit Bat Conservation International (Dr. Iudica’s article in the Spring 1999 issue of their magazine discusses how he used bats to help people in Argentina become more conservation minded) and Exploring Nature.

For more information about little brown bats visit Bat Conservation International (Dr. Iudica’s article in the Spring 1999 issue of their magazine discusses how he used bats to help people in Argentina become more conservation minded) and Exploring Nature.

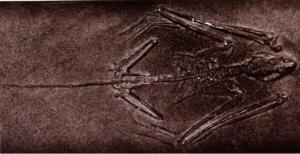

Thank you to Dr. Carlos A. Iudica. He shared his photos for this post. Here is a photo he took of a bat fossil in Wyoming. The oldest fossils of bats are from the Eocene which was about 50 million years ago. This fossil is from this timeframe.

Wood Frogs

Wood Frogs

Now that the weather is warming and the winter’s  ice is melting wood frogs are emerging to mate and lay their eggs. The male wood frogs’ duck-like quacking calls can be heard where there are seasonal pools or wetlands in wooded areas. Often the pools contains large numbers of calling males; the females, apparently attracted to the calls, make their way to the pools where the males quickly grasp them in a nuptial

ice is melting wood frogs are emerging to mate and lay their eggs. The male wood frogs’ duck-like quacking calls can be heard where there are seasonal pools or wetlands in wooded areas. Often the pools contains large numbers of calling males; the females, apparently attracted to the calls, make their way to the pools where the males quickly grasp them in a nuptial  embrace called amplexus. Wood frogs are normally a shade of brown with a darker, almost black, raccoon-like mask; they spend the warm months feeding on the forest floor. Wood frog egg masses are gelatinous masses in seasonal pools; as the embryos grow they appear as black spots within the eggs.

embrace called amplexus. Wood frogs are normally a shade of brown with a darker, almost black, raccoon-like mask; they spend the warm months feeding on the forest floor. Wood frog egg masses are gelatinous masses in seasonal pools; as the embryos grow they appear as black spots within the eggs.

April is National Frog Month

April is National Frog Month to honor the amphibians we call frogs. Of course we’re going to celebrate at NPC!

April is National Frog Month to honor the amphibians we call frogs. Of course we’re going to celebrate at NPC!

This month, you can expect information on these primitive creatures. To start the celebration we’ll cover some frog basics. Frogs typically live in moist environments and undergo metamorphosis from larvae to adults. All of our native frogs begin life from eggs that are laid in water and progress through an aquatic tadpole (larval) stage during which they do not have legs finally transforming into adults which may spend much of their life on dry land but always need to keep their skin at least somewhat moist. Adult frogs normally spend the colder months buried in the mud at the bottom of ponds or other wetlands.

Worldwide frogs are in trouble as their populations are being decimated by a chytrid fungus, although not all species or individuals within a species are equally susceptible to the disease. There is no known treatment or cure for the disease and it appears to be spreading into new areas. To learn more about the fungus visit this Wikipeida page.

Happy First Day of Spring!

Happy first day of Spring! If you’re in northcentral  Pennsylvania it’s probably snowing outside your window and not looking very spring-like. The photo was taken this morning in my yard. So, while the piles of snow are gone, there is again snow falling to the ground.

Pennsylvania it’s probably snowing outside your window and not looking very spring-like. The photo was taken this morning in my yard. So, while the piles of snow are gone, there is again snow falling to the ground.

While you’re waiting for the snow to accumulate enough to go shovel, take a look at an article from February 1941. Popular Science published an article about an effort by 35,000 amateur scientists to observe and record information about the natural world around them.

As part of the study, 200 of the participants watched and tracked 30 species of wildflowers. They noted various milestones of the plants, including when the flowers first bloomed. The northern edge of the study area was 60 miles from the southern edge. They calculated spring moved north at 10 miles a day. The flowers at the southern edge bloomed 6 days before the same species at the northern edge.

They also tracked the speed spring moves up hills or mountains. From their observations, they calculated spring gains about 100 feet in elevation each day. So, if you had a hill 200 feet high, the spring plants at the base would bloom, then 2 days (200 feet divided by 100 feet per day) later, the same species at the top of the hill would bloom.

The article is pretty interesting and has some great photos. You might want to check it out!

Happy Spring from NPC!!

Learn About Butterflies Day – March 14

March 14 is Learn about Butterflies Day! What do you know about butterflies? When I asked Charlie to share some of his knowledge and photos about butterflies, this is what he gave me….

Butterfly or Moth???

The order of insects called Lepidoptera is comprised of the creatures we call butterflies and moths, those broad-winged fliers that often seem to float along as they fly. The name Lepidoptera means “scale wing”, as the wings of almost all species are covered with fine scales.

Although there are many similarities, there are also significant differences between butterflies and moths. In general, butterflies are active during daylight while moths, with a few exceptions, are active at night. The antenna of butterflies are slender and club-like while those of moths resemble feathers (the antenna of  male moths are usually larger and more “feathery” than the antenna of females). While only a few species of butterflies appear to be drab gray or brown, many species of moths are various shades of tan, brown or gray. Resting butterflies tend to hold their wings vertically over their backs while moths usually hold their wings horizontally.

male moths are usually larger and more “feathery” than the antenna of females). While only a few species of butterflies appear to be drab gray or brown, many species of moths are various shades of tan, brown or gray. Resting butterflies tend to hold their wings vertically over their backs while moths usually hold their wings horizontally.

Charlie’s photos above highlight the antenna of a butterfly (left) and a moth (right).

First of the Year

Soon they will emerge, the first butterflies of the year – the mourning cloaks. Occasionally there may still be patches of snow in shady areas, but on warm days of early spring mourning cloaks will emerge from hibernation. These are the only butterflies in our area that actually hibernate as adults, spending the winter in tree cavities or beneath loose bark. Mourning cloaks mate in spring after which the females lay their eggs on the host plats on which the larvae will feed – willow, wild rose, hawthorn and a number of other species. After the larvae have matured, they pupate, transforming into adult butterflies which emerge in June and July. The adults estivate (which can be thought of as summer hibernation) and emerge again in the fall to feed and store energy for winter hibernation. When the mourning cloaks emerge we know spring has arrived.

Soon they will emerge, the first butterflies of the year – the mourning cloaks. Occasionally there may still be patches of snow in shady areas, but on warm days of early spring mourning cloaks will emerge from hibernation. These are the only butterflies in our area that actually hibernate as adults, spending the winter in tree cavities or beneath loose bark. Mourning cloaks mate in spring after which the females lay their eggs on the host plats on which the larvae will feed – willow, wild rose, hawthorn and a number of other species. After the larvae have matured, they pupate, transforming into adult butterflies which emerge in June and July. The adults estivate (which can be thought of as summer hibernation) and emerge again in the fall to feed and store energy for winter hibernation. When the mourning cloaks emerge we know spring has arrived.

Puddling

Anyone who spends time outdoors in the spring or summer will, from time to time, see collections of butterflies gathered around damp spots or on animal or bird droppings. These aggregations are usually comprised of male butterflies and close observation will reveal that the butterflies proboscises are often extended and contacting the damp soil or feces. These butterflies are doing what is called “puddling”, a process whereby they drink and/or acquire  the minerals they need to survive.

the minerals they need to survive.

Butterflies can be attracted to a home garden not just by nectar producing flowers, but by an area where they can puddle. A suitable puddling spot can be made by partially filling a large flower pot saucer with soil to which a bit of salt has been added and then keeping the soil very damp; placing a few flat stones on the soil surface will give the butterflies a place to bask, especially if the puddling spot is in the sun.

Tufted Titmouse – February is Feeding Birds Month

Fifty years ago it was an unusual occurrence to have a number of tufted titmice visiting a feeder in northcentral Pennsylvania every day. Following a hard winter they might disappear for a year or more until young birds wandering into territories unoccupied since the death of the previous residents re-established a population. As winters have warmed over the last few decades the tufted titmouse, generally considered a southern species, have become permanent and common residents of woodlands, fencerows, brushy fields and suburban areas in northcentral Pennsylvania. Titmice frequently are members of feeding cohorts which include chickadees, nuthatches, and downy woodpeckers – each species feeds on similar food items but has a different method of foraging and thus don’t actually compete for food.

But, if we think of bird feeders as the avian equivalent of a fancy restaurant it should be readily apparent that feeders are not the be-all and end-all of what these birds need. They also need a place to live – correctly called habitat. That habitat must include winter roosting sites and nesting site, both being tree hollows or similar cavities, as well as other sources of food including insects and cover in which to escape inclement weather and predators.

But, if we think of bird feeders as the avian equivalent of a fancy restaurant it should be readily apparent that feeders are not the be-all and end-all of what these birds need. They also need a place to live – correctly called habitat. That habitat must include winter roosting sites and nesting site, both being tree hollows or similar cavities, as well as other sources of food including insects and cover in which to escape inclement weather and predators.

The Cornell Lab of Ornithology has a recording of the tufted titmouse’s song on their website. If you visit National Geographic’s website you’ll see drawings of a juvenile and adult as well as a map showing their range.

Mourning Doves – February is Bird Feeding Month

Mourning doves are ungainly on the ground as they walk about on their short legs, often with their heads bobbing. But, oh are they graceful in the air – speedy too.

Mourning doves are ungainly on the ground as they walk about on their short legs, often with their heads bobbing. But, oh are they graceful in the air – speedy too.  Mourning doves are seed eaters; although they have difficulty actually using most bird feeders, they can often be seen on the ground beneath a feeder eating spilled seed. Unlike most birds, mourning doves in warm climates may breed during any month of the year, building a flimsy nest of twigs. Dependent on somewhat open habitat, mourning doves may be found almost anywhere in the country except in dense unbroken forest. They were named for the soulful sound of their cooing and may be heard in the background of many Hollywood movies and TV shows, especially old westerns.

Mourning doves are seed eaters; although they have difficulty actually using most bird feeders, they can often be seen on the ground beneath a feeder eating spilled seed. Unlike most birds, mourning doves in warm climates may breed during any month of the year, building a flimsy nest of twigs. Dependent on somewhat open habitat, mourning doves may be found almost anywhere in the country except in dense unbroken forest. They were named for the soulful sound of their cooing and may be heard in the background of many Hollywood movies and TV shows, especially old westerns.

Downy Woodpecker

February is National Feed a Bird Month. Charlie was kind enough to share some of his bird knowledge and photos.

Downy woodpeckers are our smallest woodpecker and like chickadees are found in a wide variety of habitats. They are common in residential neighborhoods that contain fairly large trees where they nest in small cavities that they excavate in soft or decaying wood. Also like chickadees, they spend winter nights in cavities where they are protected from cold temperatures and chilling winds. Downy woodpeckers will visit feeders to feast on suet and peanut butter and will even eat corn and sunflower seeds by wedging them in bark crevices and pounding them open. Along with chickadees, titmice, nuthatches and brown creepers, downy woodpeckers will form a feeding cohort that travels through woodland. Each species in the cohort has a different feeding strategy and thus does not compete against the others. Male downy woodpeckers have a small red spot on the back of their heads, which females lack.

The Cornell Ornithology Lab has more information and recordings so you can hear the song. You can also visit National Geographic’s website or Audubon for more downy woodpecker information.

Northern Cardinals

February is National Bird Feeding Month. To celebrate, each Monday, NPC will post information on some of the more “popular” backyard birds. Thank you to Charlie for writing the posts, and providing the photos.

Northern cardinals are usually the most colorful birds to visit backyard feeders where they feast on sunflower and other seeds. Male cardinals are bright red beneath and brownish red on their backs; females are much more brown which offers better concealment when they incubate their eggs in an open nest in dense shrubbery. Cardinals prefer brushy habitat dominated by shrubs and small trees; that is why they are fairly common in residential neighborhoods containing many shrubs. Males sing loudly in spring and females also occasionally sing. Cardinals are crepuscular meaning that they are most active at dawn or dusk; they are often the last birds to visit a feeder in the evening. As the climate changes and winters get warmer, cardinals have been extending their range northward into northern New England and southern Canada.

Northern cardinals are usually the most colorful birds to visit backyard feeders where they feast on sunflower and other seeds. Male cardinals are bright red beneath and brownish red on their backs; females are much more brown which offers better concealment when they incubate their eggs in an open nest in dense shrubbery. Cardinals prefer brushy habitat dominated by shrubs and small trees; that is why they are fairly common in residential neighborhoods containing many shrubs. Males sing loudly in spring and females also occasionally sing. Cardinals are crepuscular meaning that they are most active at dawn or dusk; they are often the last birds to visit a feeder in the evening. As the climate changes and winters get warmer, cardinals have been extending their range northward into northern New England and southern Canada.

Audubon and National Geographic both have some great information on the Northern Cardinal and its range. You can also visit the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s YouTube channel to hear the Northern Cardinal’s song.