By: Susan Sprout

As above, so below. Looking downward, I saw the stars! Five to nine smooth, lance-shaped leaves were whorled around a thin stem, some in double tiers, looking like stars scattered about on the shady forest floor. The Indian Cucumber Root (Medeola virginiana) I found along the Double Run Nature Trail at Worlds End was blooming…a delightful experience to behold!

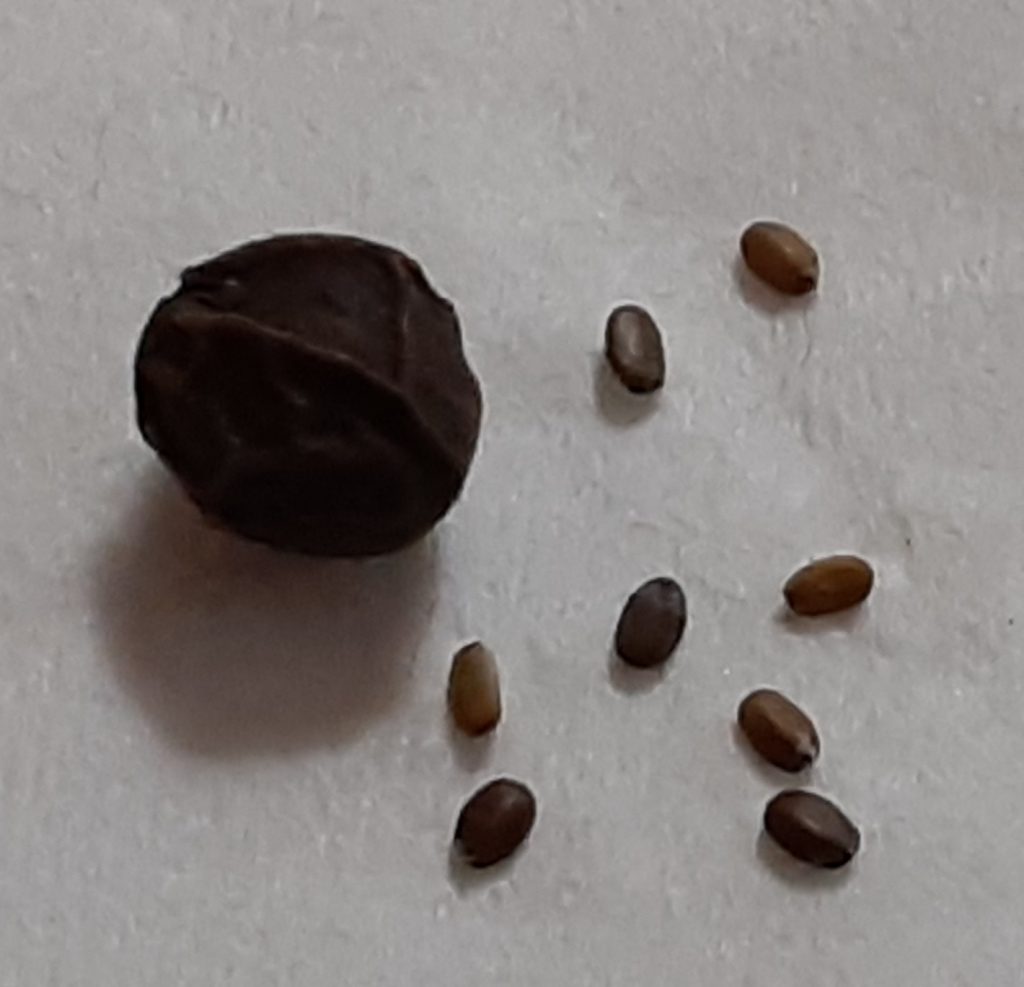

Greenish-yellow flowers, one or two, hang on drooping stems beneath circles of leaves, their petals curved back showing their long, brown styles that carry pollen to the ovaries where purple to black berries will eventually form. Parallel leaf veins speak to their ties with the Lily Family, Lilaceae. The cucumber part of the common name comes from the two to three inch long tuberous white root that smells and tastes like cucumbers. Native Americans gathered them as food, a labor not recommended today because of the scarcity of this native plant.

There were other “stars” in the Double Run woods that day, June 12, 2021. DCNR Secretary Cindy Adams Dunn, Deputy Secretary for Parks and Forestry John Norbeck, Worlds End Park employees and Friends of the Park were there along with others who gathered to witness the dedication and induction of the park’s 780 acres into the Old-Growth Forest Network. Dr. Joan Maloof, founder and director of the network presented a commemorative sign and spoke about the importance of protecting older forests, at least one in every county of every state in the US, building not only a network of forests, but also an alliance of people who care about forests. Eighteen PA counties have old-growth forests placed in the network so far. Article 1, Section 27 of the Pennsylvania State Constitution states that people have a right to clean air, pure water, and the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic, and esthetic values of the environment. DCNR as a caretaker of these resources for citizens now and generations to come, sees the conservation and maintenance of them as their mission. BRAVO!