Pennsylvania is home to some of the best trout fishing in the world! Excited anglers from across the state will soon gear up to fish their favorite spots on during the traditional statewide opening day of trout season. In celebration of this long awaited highlight of spring, let’s talk trout!

Three different trout species can be found in PA waters – Brook, Brown, and Rainbow. Let’s start by getting to know each of them a little better.

Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis)

The brook trout is Pennsylvania’s official state fish. It is technically a type of char belonging to the salmon family, Salmonidae. The brook trout—also called the speckled trout—is a beautifully colored fish with yellow spots over an olive-green back. The spots along the trout’s back are stretched and almost wormlike in shape. Along its sides, the brook trout’s color transitions from olive to orange or red, with scattered red spots bordered by pale blue. Its lower fins are orange or red, each with a white streak and a black streak, and its underside is a milky white. A brook trout usually reaches 9 to 10 inches in length.

They are often found in clean, cool mountain streams and are most active around dawn and dusk. During the day, brook trout may retreat to deeper waters.

These fish are extremely opportunistic and eat a variety of insects, often preferring adult and nymph forms of aquatic insects. They will also eat beetles, ants, and small fish when they are available.

Fun Fact: The biggest Brook Trout of state record, weighing in at a whopping 7lbs, was caught right here in North Central Pennsylvania, at Fishing Creek in Clinton County!

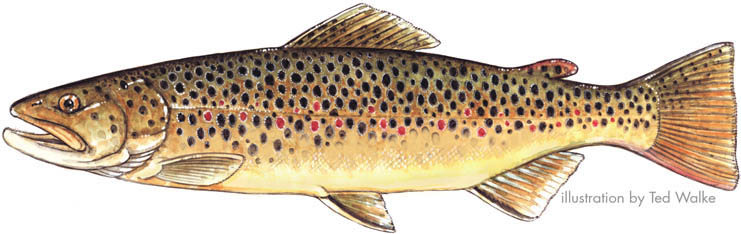

Brown Trout

(Salmo trutta)

The brown trout is not a native Pennsylvanian, although it is now naturalized and widespread here in the wild. Brown trout are brownish in overall tone. The back and upper sides are dark-brown to gray-brown, with yellow-brown to silvery lower sides. Large, dark spots are outlined with pale halos on the sides, the back and dorsal fin, with reddish-orange or yellow spots scattered on the sides. The fins are clear, yellow-brown, and unmarked. Wild Brown Trout in infertile streams may grow only slightly larger than the Brook Trout there. But in more fertile streams Brown Trout that weigh a pound are common. A Brown Trout over 10 pounds is a trophy. Brown Trout may exceed 30 inches in length. The state record is more than 19 pounds.

They may be found in all of the state’s watersheds, from limestone spring creeks, infertile headwaters and swampy outflows to suitable habitat in the larger rivers and reservoir tailwaters.

These fish eat aquatic and terrestrial insects, crayfish and other crustaceans, and especially fish. The big ones may also eat small mammals (like mice), salamanders, frogs and turtles. Large Browns feed mainly at night, especially during the summer.

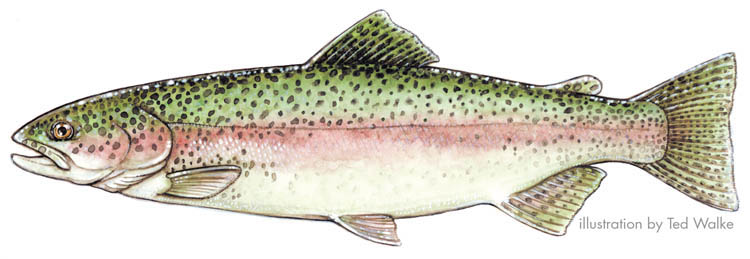

Rainbow Trout

(Oncorhynchus mykiss)

The rainbow trout is native only to the rivers and lakes of North America, west of the Rocky Mountains, but was introduced to PA at the turn of the century. Rainbow trout are gorgeous fish, with coloring and patterns that vary widely depending on habitat, age, and spawning condition. They are torpedo-shaped and generally blue-green or yellow-green in color with a pink streak along their sides, white underbelly, and small black spots on their back and fins. They average about 20 to 30 inches long and around 8 pounds. The state record is 20 pounds.

They prefer cool, clear rivers, streams, and lakes, though some will leave their freshwater homes and follow a river out to the sea. These migratory adults, called steelheads because they acquire more silvery markings, will spend several years in the ocean, but must return to the stream of their birth to spawn.

Rainbow trout survive on insects, crustaceans, and small fish.

You can help work on projects to create more access to creeks and streams and rivers for fishing, paddling and splashing. You can create more access to trails for walking and birding and biking and skiing.

You can help work on projects to create more access to creeks and streams and rivers for fishing, paddling and splashing. You can create more access to trails for walking and birding and biking and skiing.  “March Madness” may refer to college basketball playoffs, but at NPC it’s Macro Madness.

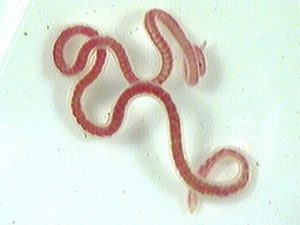

“March Madness” may refer to college basketball playoffs, but at NPC it’s Macro Madness. These worms are pollution tolerant, meaning they can live in polluted water. Their body is soft, cylindrical, and long – like the earthworms you find in your yard or on pavement after a summer rainstorm. The body is divided into many segments (usually 40-200).

These worms are pollution tolerant, meaning they can live in polluted water. Their body is soft, cylindrical, and long – like the earthworms you find in your yard or on pavement after a summer rainstorm. The body is divided into many segments (usually 40-200). Midge Larvae are another pollution tolerant species. Midges are small insects that look like mosquitoes, but don’t bite. Midges, like a lot of insects, go through various life stages.

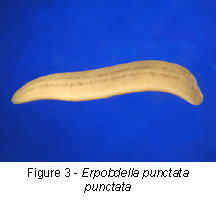

Midge Larvae are another pollution tolerant species. Midges are small insects that look like mosquitoes, but don’t bite. Midges, like a lot of insects, go through various life stages. Leeches can live in polluted water. They are considered a pollution tolerant taxa.

Leeches can live in polluted water. They are considered a pollution tolerant taxa. “Mr. Speaker, I would like to recognize February, one of the most difficult months in the United States for wild birds, as National Bird-Feeding Month. During this month, individuals are encouraged to provide food, water, and shelter to help wild birds survive. This assistance benefits the environment by supplementing wild bird’s natural diet of weed seeds and insects. Currently, one third of the U.S. adult population feeds wild birds in their backyards.”

“Mr. Speaker, I would like to recognize February, one of the most difficult months in the United States for wild birds, as National Bird-Feeding Month. During this month, individuals are encouraged to provide food, water, and shelter to help wild birds survive. This assistance benefits the environment by supplementing wild bird’s natural diet of weed seeds and insects. Currently, one third of the U.S. adult population feeds wild birds in their backyards.” Peanuts are another bird favorite. Blue jay, downy woodpecker, red-bellied woodpecker, tufted tit-mouse, black-capped chickadee, cardinal, among others are the birds you can expect to see eating peanuts or peanut pieces at your feeder. Something to keep in mind, however, is squirrels also like peanuts. And while we like squirrels, we understand they can create problems.

Peanuts are another bird favorite. Blue jay, downy woodpecker, red-bellied woodpecker, tufted tit-mouse, black-capped chickadee, cardinal, among others are the birds you can expect to see eating peanuts or peanut pieces at your feeder. Something to keep in mind, however, is squirrels also like peanuts. And while we like squirrels, we understand they can create problems. You can also use a hummingbird feeder. The feeder is filled with a syrup of one part granulated sugar to four parts water. You’ll need to heat water then add sugar, stirring until it dissolved. Let the mixture cool before filling your feeder.

You can also use a hummingbird feeder. The feeder is filled with a syrup of one part granulated sugar to four parts water. You’ll need to heat water then add sugar, stirring until it dissolved. Let the mixture cool before filling your feeder.

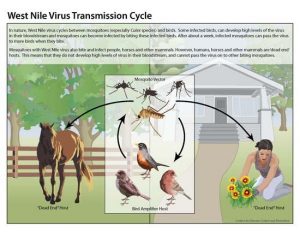

The West Nile virus can infect humans, birds, mosquitoes, horses, and some other mammals. Humans get West Nile from the bite of an infected mosquito. The virus occurs in late summer and early fall in mild zones like Pennsylvania.

The West Nile virus can infect humans, birds, mosquitoes, horses, and some other mammals. Humans get West Nile from the bite of an infected mosquito. The virus occurs in late summer and early fall in mild zones like Pennsylvania.