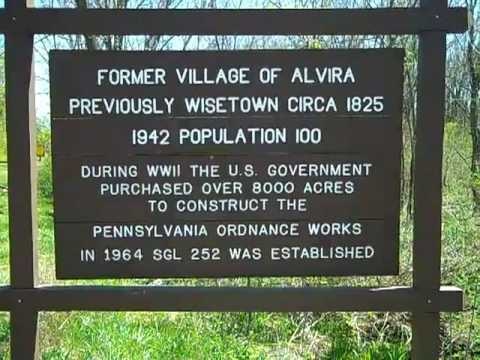

The War Department condemned the town of Alvira in Union County, PA in 1942 in order to establish a munitions manufacturing facility. Known locally as “the Ordnance,” the site used water drawn out of the West Branch Susquehanna River below Montgomery to manufacture munitions for the war effort during World War II.

Eighty years later, the Northcentral Pennsylvania Conservancy worked with the Pennsylvania Game Commission, Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission, Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and Union County Conservation District to stop the erosion created by establishing the Ordnance.

After the residents of Alvira were gone, the structures in the community were torn down and burned with the exception of a stone church. The Pennsylvania Ordnance Works was established and production got underway.

During the process of establishing the Pennsylvania Ordnance Works, a perimeter road was built. Presumably for security and to allow the property boundaries to be patrolled and secured.

That road was built in a straight line. Spring Creek which flows through the southern side of the Ordnance does not flow in a straight line. It bends and turns and twists back.

The straight road cut off an oxbow, or u-shaped bend, in Spring Creek from the flowing stream channel. By looking at aerial photos from the 1930s and today you can see the large wetland that developed where the oxbow was.

Streams are stubborn. If they want to bend and wiggle, they will flow and cut and erode their way into the bend and wiggle they want.

That’s what happened here. Over time, the now channelized Spring Creek was eroding the streambanks as it was trying to get some of its bend back.

In the late 2010s the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC), Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and Union County Conservation District (UCCD) looked at the site and developed a design to help stabilize the streambanks and improve access to the stream.

This stretch of Spring Creek is on State Game Lands 252. After World War II the property taken for the Ordnance was divided up. Just over 3,000 acres was used to established State Game Lands 252 in 1964.

Since State Game Lands are open for public recreation and this stretch of Spring Creek is stocked there is a lot of fishing activity on the property. The activity was pretty concentrated in a couple of spots because it was difficult to get to the stream. The perimeter road, now used as a management road by the Game Commission, creates a steep side that isn’t easy to get up and down.

With a design in hand the group waited until funding could be found to support the project. That funding was found in late 2021. The plan was dusted off and updated. Streams can change a lot year to year and this stream had over 5 years to change.

The site was added to the schedule for the 2022 construction season and additional grant funding was secured through Keep Pennsylvania Beautiful’s Healing the Planet Grant Program with support from The GIANT Company.

The first two weeks of August were set aside for the project. The team wanted the water levels down and August is typically dryer with lower water levels. There are some deep holes in the stream and we didn’t want those to be problematic for construction. Another reason to wait until August – there’s less activity on this area of the State Game Lands. The crew saw a trail runner a few times and a couple of horseback riders, but we weren’t interfering with their recreation.

Before we got on site, the Game Commission’s crew brushed out the area to make it easier to work and to help set the stage for a tree planting. They set some of the trees so they could be used in the structures and built brush piles with some (we not only create fish habitat, but we also caused rabbit habit to be created).

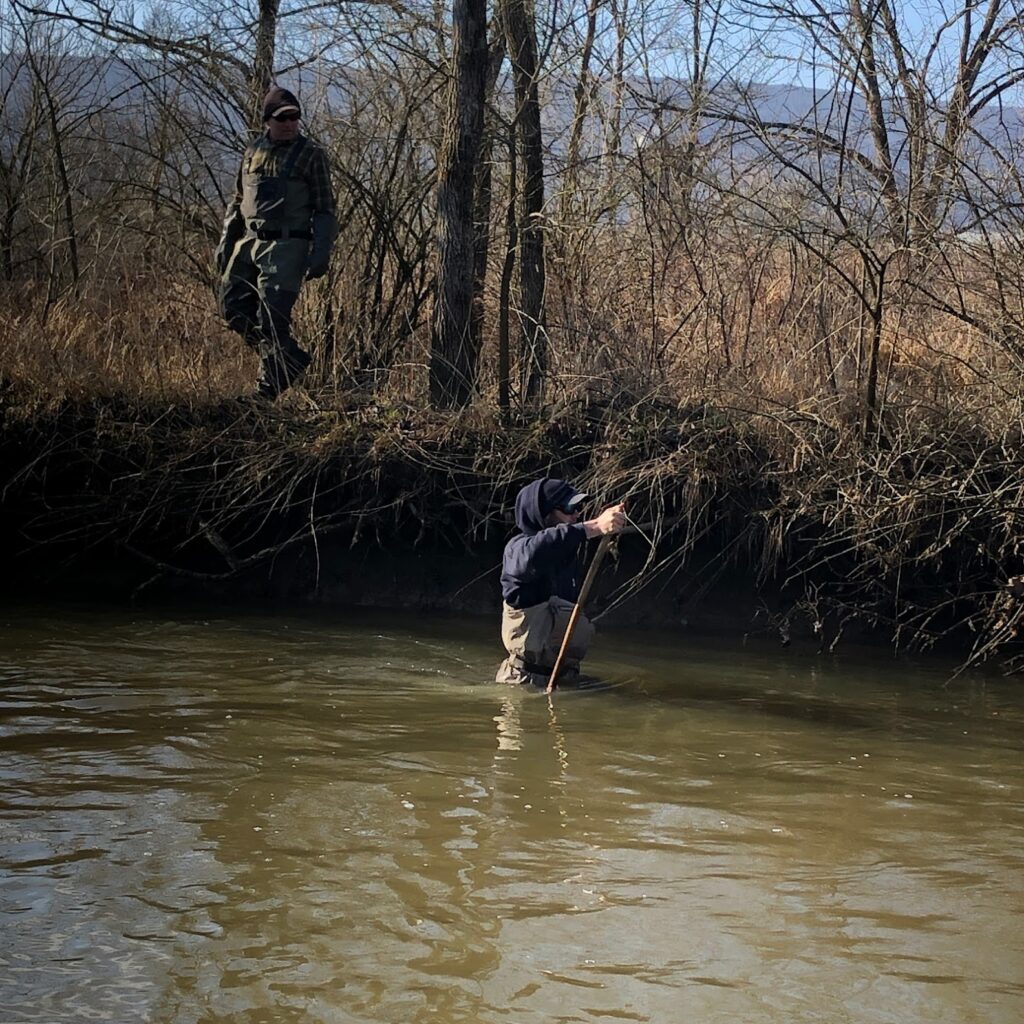

The team started upstream and worked downstream installing the log and rock structures.

It really didn’t take long for fish to move in. The first couple of days the team wasn’t seeing much, by the end of the project the group was seeing more fish overall and a greater variety of fish species.

The contractor did a great job with the bank full benches. These areas allow the stream to spread out in high water, slowing down the water’s speed and reducing the erosion. They also create areas where people can stand and fish. The group worked to ensure the bank leading to the bank full bench was sloped in a way to make it easier to walk down and get to the stream’s edge.

Things will be given a year or two to settle in and then more trees and shrubs will be planted. These plants will help shade the stream to keep summer temperatures cooler, and the roots of the plants will provide additional stabilization.

Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission Executive Director Tim Schaeffer stopped by on the last day of construction. It was a great opportunity to highlight the teamwork needed to get projects on the ground.

If you use State Game Lands 252 stop by and let us know what you think of the project.

If you’re interested in learning more about Alvira Robin Van Aucken and the Montgomery Historical Society have sites that may be helpful.