By: Sue Sprout

Whether it is pronounced “soo-mack” or “shoo-mack”; whether it is known as Velvet Sumac, Staghorn Sumac, or scientifically as Rhus typhina; whether people call it a tall shrub or a small tree – it is what it is! And, it is a native (to Eastern N.A.), non-poisonous, deciduous, furry-limbed plant with amazing pyramid-shaped, hairy, red seed heads that stay on during the winter months to provide food for over 30 species of birds and small mammals. Whew! I feel like that should do it. Alas, I suspect some explanation is required.

What’s in a name? The fact that historically leaves and fruits were boiled to make black dye used in tanning leather and a waxy substance used for shining shoes may explain the “shoo-mack” pronunciation.

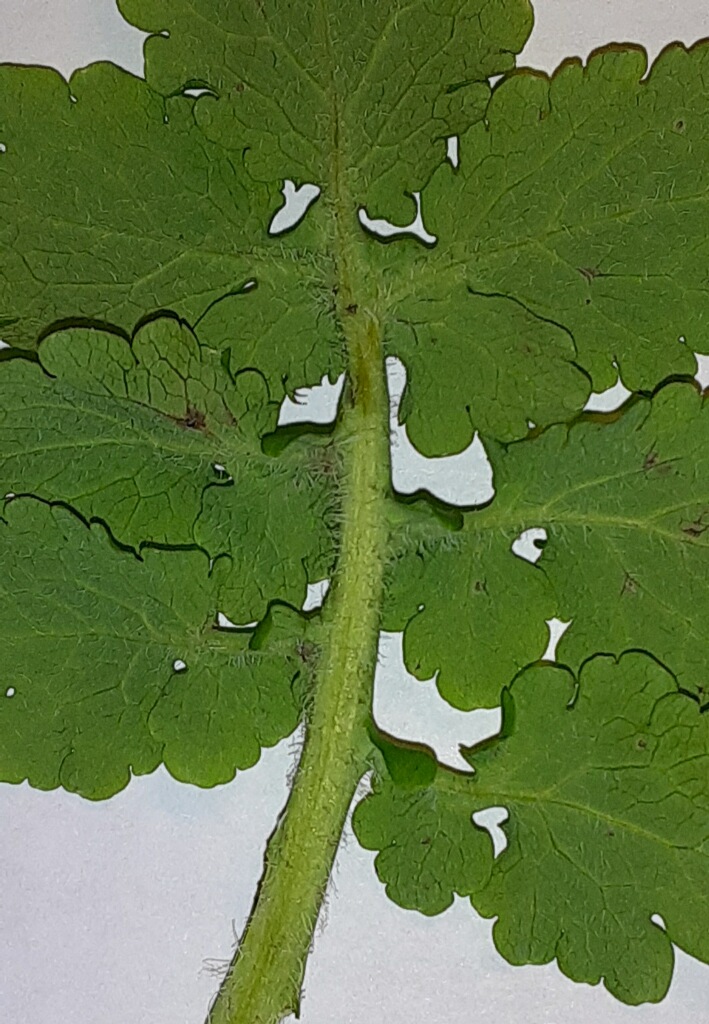

Deer antlers, as they develop, are covered by a nourishing layer of skin covered with short hairs (the velvet) and small blood vessels that carry the nutrients and minerals for growing bone. The trunk and stems of this plant are covered with short, soft hairs with a furry touch like velvet that resemble the growing antlers of deer. Thus, the use of the common names Staghorn Sumac and Velvet Sumac.

The species name typhina refers to deer antlers. The name Rhus refers to the whole genus of sumacs (about 35 kinds worldwide) where they are all members of the ANACARDIACEAE or Cashew family, along with some other plants you may recognize: pistachios, cashews, mangos, poison ivy, poison oak, and poison sumac. Here is where the sad fact of misidentification or misnaming becomes apparent. There is another plant commonly named Poison Sumac that has smooth bark and white berries as seeds that hang down under the leaves. It is found growing in wetter areas than our Staghorn likes (most of the time). It is in a different genus grouping known as Toxicodendron along with its itchy relatives. Do you see the word “toxic” in their family name? None of them contain a poison, but rather, a very potent allergen that makes susceptible people who touch their leaves, stems or roots, get a contact dermatitis. Our Staghorn Sumac is non-poisonous.

Look for Staghorn Sumacs along the backroads you travel, with large seed clusters sticking up above where their leaves used to be. These trees are deciduous and shed their leaves in the fall. Sometimes the smaller shrubs in the colonies formed by their spreading roots will retain their bright yellow, orange or red leaves longer. If you get a chance, look at the seeds. In June and July, hundreds to thousands of small yellow to greenish five-petaled flowers attracted many bees, wasps and beetles that spread their pollen around to create these big red clusters of hairy seeds. Look at them with a magnifier. Tiny red Muppets.

Medicinally, the seeds of this plant were removed from their stems and soaked like sun tea until the water turned red as the ascorbic acid in the red hairs seeped out, then strained through cloth so people didn’t actually drink the red hairs (or the bugs that lived in or among them). It was administered as a “refrigerant” or a cooling drink to those suffering from heat problems. It is bitter like lemonade without the sugar. This beverage was used a lot in hospitals during the Civil War. Back as far as 2000 years, Sumac was noted for its medicinal properties as a diuretic.

“Summaq” is an Arabic word for dark red. I use a spice mixture called Za’atar when I cook Middle Eastern dishes. The red berries of a species of Summaq that grows on the high plateaus of the Mediterranean region are ground and mixed with thyme and other herbs to provide a tartness that brings out the flavor of foods it is cooked with. BTW, the Emperor Nero used it as an anti-flatulent. TMI?

Susan Sprout is an environmental educator and long-time, loyal member of NPC. Learn more about the author here.