Beneath the surface of our streams, rivers, and ponds, a hidden world teems with tiny creatures that reveal a lot about the health of our waters. These creatures, known as aquatic macroinvertebrates, might be small, but they are mighty indicators of water quality.

What Are Macroinvertebrates?

Macroinvertebrates, or macros, are small creatures that are visible to the naked eye and do not have a backbone. Aquatic macros live in all kinds of water, from fast mountain streams to slow, muddy rivers and ponds. Examples include insect larvae, clams, snails, and worms. Many of these creatures spend part or all of their lives on submerged rocks, logs, and plants.

Why Use Macroinvertebrates as Indicators?

The health of a water body often reflects the life it supports. Macroinvertebrates are sensitive to changes in their environment, making them valuable indicators of water quality. Their presence, abundance, and diversity provide important clues about the condition of their aquatic habitat:

- Pollution Sensitivity: Some macroinvertebrates are very sensitive to pollutants like excess nutrients, sediments, or toxins. A drop in their numbers can signal deteriorating water quality, while an increase can indicate improvements (see NPC’s Turtle Creek project!).

- Habitat: Different species thrive in different conditions. By identifying which species are present, biologists can infer habitat conditions such as oxygen levels or sedimentation.

- Long-Term Indicators: Unlike fish, which may migrate or have varying tolerances, macroinvertebrates are generally sedentary. Their presence reflects long-term environmental conditions.

- Collection: They are relatively easy to identify and collect using simple methods.

How Biologists Collect Samples

The EPT Index is a key tool used to assess stream and river quality by examining the presence and diversity of three groups of aquatic macros: mayflies (Ephemeroptera), stoneflies (Plecoptera), and caddisflies (Trichoptera). Here’s how it works:

- Sampling: Biologists collect samples of aquatic insects from stream or riverbeds. These samples may include larvae and nymphs of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies, as well as other species.

- Identification: The collected insects are sorted and identified to determine which species are present.

- Assessment: The number and types of each insect species are counted. The data is used to calculate the EPT Index. A high number of different species of mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies indicates good water quality, as these insects are sensitive to pollution.

- Understanding: Streams with many different kinds of these insects have high water quality. Streams with fewer sensitive species and more pollution-tolerant species suggests lower water quality.

The EPT Index helps monitor and manage water quality in Pennsylvania by providing a clear picture of the health of our waters.

Meet the Mayflies, Stoneflies, and Caddisflies

Let us take a closer look at these pollution-intolerant water insects:

Mayflies (Order Ephemeroptera):

Mayflies are a favorite food for trout and have a brief adult lifespan, often living just a few hours to a day. They have delicate wings and long, slender bodies. Their nymphs are flattened and have gills along the abdomen. They are good indicators of water quality because they are sensitive to pollution and require clean-oxygen-rich water to survive.

Stoneflies (Order Plecoptera):

Stoneflies are commonly found in running waters, clinging to boulders, cobbles, water-soaked wood, and leaf packs. Most species are either predators or shredders, feeding on decaying plant material. The presence of stoneflies indicates excellent water quality. However, their absence does not always mean pollution; it could just mean the specific habitat conditions they need aren’t present. In low-oxygen conditions, stonefly larvae do “push-ups” to move water across their gills!

Caddisflies (Order Trichoptera):

Female caddisflies lay their eggs in or just above the waterline. When the eggs hatch, larvae emerge and live underwater for up to a year, using feathery gills to breathe. Some species of larvae build protective cases from materials like sand, gravel, leaves, and twigs, which offer camouflage and protection from predators. While net-spinning caddisfly larvae build nets to collect detritus (leaf particles) to eat as they flow downstream. After pupating, they transform into winged adults and live for about a month. The presence of caddisflies usually signals good water quality.

Magical Macros & the Northcentral Stream Partnership

By studying these tiny indicators, biologists can gauge the health of our waters and help direct conservation efforts. As part of the Northcentral Stream Partnership, the Northcentral Pennsylvania Conservancy (NPC) collaborates with state agencies, county conservation districts, and landowners to restore the health of impaired streams in our region. Through various streambank stabilization projects, we work to decrease erosion, reduce pollution, enhance habitat for aquatic life, and stabilize banks with native plantings.

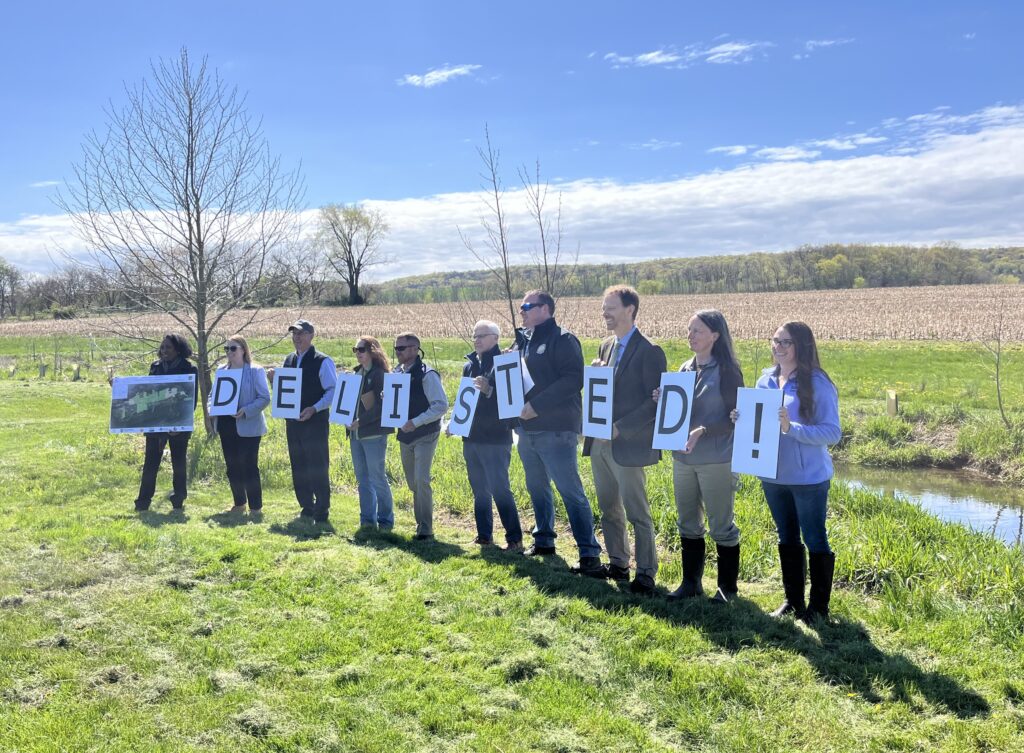

In early 2024, two segments of Turtle Creek were removed from Pennsylvania’s list of impaired waters after being resampled by biologists. The sampling revealed a comeback of our favorite macros—mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies! This wasn’t by magic, but rather the result of teamwork, consistent effort, and the support from the NPC membership. So, the next time you spot a mayfly drifting on the surface or a caddisfly case nestled in the sediment, take a moment to relax—you’re in healthy water!