By Susan Sprout

I have been looking for this plant. It can bloom from July to October, depending on where it grows. And depending on where I look since it is a native in North America all the way from Labrador to Georgia and Louisiana. According to a Pennsylvania native plant site on-line, it has been found growing in every county in our state. I finally found mine in disturbed soil under a shady Spruce tree in Lycoming County!

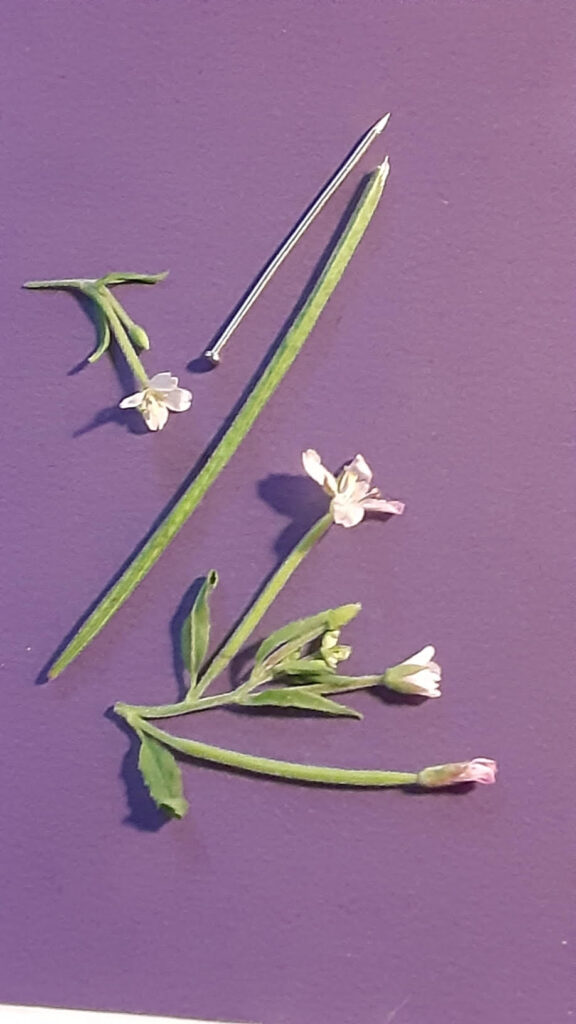

Indian Tobacco is definitely not showy like its two-to-four-foot-tall bright red relative Cardinal Flower (Lobelia cardinalis) that decorates stream banks and wetlands. Or its three-to-four-foot-tall bright blue relative Great Lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica), a plant I wrote about in a previous post. All three are members of the Bellflower Family and have tube-type flowers with five thin, pointed lobes – two at the top resembling ears extending upward and three on the bottom edge sticking out like lower lips.

Indian Tobacco is a thinner and much less robust-looking plant at three feet tall with ½ inch pale lavender to white flowers. Each flower tube is cupped at the bottom by a green leafy calyx with five thin green points that extend out beyond the lobes of the flower. Here is the totally cool thing about the cup on the bottom of the flower tube – it is where the seeds develop after pollination has taken place AND it is where the species name, inflata, comes from. As the fruits grow and swell, they morph or inflate into round capsules measuring about 3/8th inch and look like tiny balloons tied on the stems. When mature and dried, the balloons will burst and give seeds to the wind!

The simple leaves of Indian Tobacco can be hairy on both sides. They grow alternately on the plant stem that can be hairy, too. They are oval and range from 1 to 2 1/2 inches in length. Another feature that may catch your eye is the leaves’ toothed edges that have white dots on them. Surprise! I do not know, maybe it is the plant’s milky sap oozing out the tips.

The common name, Indian Tobacco, comes from native populations’ documented use of the leaves for smoking as a tobacco, by itself or mixed with other dried plants. Chewed leaves were also used for internal cleansing as an emetic, a practice that gave the plant another common name – Puke Plant! This plant and others in the same genus contain moderately poisonous alkaloids like lobeline. Nausea, vomiting, sweating, heart palpitations can result from its use. Beware!