Tom Baker, is a distinguished professor of entomology and chemical ecology at Penn State University. He has 40 years of experience in entomology research. He describes the spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula (WHITE)) as, “… the weirdest, most pernicious insect I’ve ever seen.”

That sounds pretty serious. Officials at the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture, Bureau of Forestry, and Penn State Extension are worried about how spotted lanternfly will impact Pennsylvania’s agriculture, tree-fruit, hardwood and nursery industries. Researchers are trying to understand if plants can recover from infestations or if the damage to trees and vines is permanent.

The spotted lanternfly is native to China, India, Japan and Vietnam. It feeds on the woody parts of plants (tree trunks, vines, tree branches). As it feeds it creates wounds on the tree or vine that allow sap to escape and the spotted lantern fly excretes a substance known as honeydew as it feeds. The honeydew and sap attract other insects and also allow for fungi to take hold and grow. Some of the most common fungi will cover leaf surfaces and stunt growth. Plants with heavy infestations generally don’t survive.

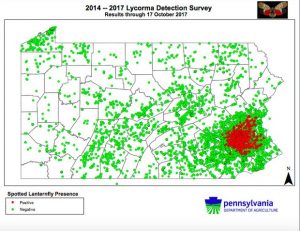

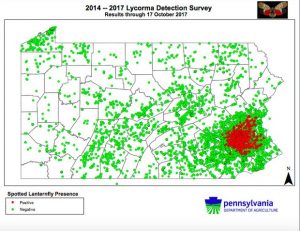

Pennsylvania has the unfortunate distinction of being the first place in the United States where the spotted lanternfly was found. The PA Department of Ag. and Pennsylvania Game Commission confirmed the insect in Berks County in 2014.

The Department of Agriculture set up a quarantine area at that time and has expanded the area each year since. One way to stop the spread of the insect and possibly be more successful with controlling it is to keep it in a smaller geographic area.

People are asked to not move or remove the following items from the quarantine area:

- Firewood of any species

- Any living stage of the Spotted Lanternfly – including egg masses, nymphs, and adults

- Brush, debris, bark, or yard waste

- Landscaping, remodeling or construction waste

- Logs, stumps, or any tree parts

- Grapevines for decorative purposes or as nursery stock

- Nursery stock of any type

- Crated materials

- Outdoor household articles including recreational vehicles, lawn tractors and mowers, mower decks, grills, grill and furniture covers, tarps, mobile homes, tile, stone, deck boards, mobile fire pits, any associated equipment and trucks or vehicles not stored indoors

So, before you decide that the tree you helped your parents or kids cut down in their yard in Litiz would be great for campfires at your house or camp in Waterville, think twice.

Before you take your brother’s old grill (because he had to buy the new one with the second side burner) and move it from his house in Reading to your deck in Danville, think twice.

Those simple actions could be moving an insect pest into central Pennsylvania that would have lasting impacts on the regions wineries, farms, and forests.

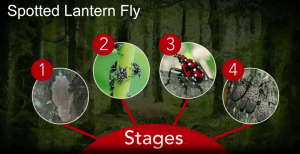

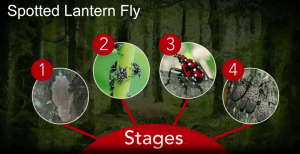

The spotted lanternfly has several life stages. If you  know what it looks like in each of those stages, you can help agricultural scientists who are working to prevent the spread and prevent further damage to Pennsylvania’s forests and farms.

know what it looks like in each of those stages, you can help agricultural scientists who are working to prevent the spread and prevent further damage to Pennsylvania’s forests and farms.

In Pennsylvania, the spotted lanternfly overwinters in egg masses. The masses are laid on smooth, vertical surfaces such as tree bark and stones.

The first stage begins emerging from the egg masses in mid-May. At this point it’s an instar (an immature stage of an insect) nymph. It’s black with white spots and no wings.

The first stage begins emerging from the egg masses in mid-May. At this point it’s an instar (an immature stage of an insect) nymph. It’s black with white spots and no wings.

As it grows it keeps the white spots and develops red patches.

Nymphs spread from their egg mass site by crawling or jumping. Spotted lanternfly aren’t really very good at flying, but are amazing jumpers. They’ll use any plant they comes across to feed and move.

Adults look very different than the nymphs and start to appear in the middle of July. As an adult they have a black head and grayish wings with black spots when they are at rest, wings tucked in. The tips of the wings are a pattern of black rectangular blocks with grey outlines. When its wings are out the Spotted Lanternfly’s hind wings are red at the base and black at the tip with a white stripe dividing them. The red portion of the wing has black spots. The abdomen is bright to pale yellow with bands of black on the top and bottom surfaces.

Adults look very different than the nymphs and start to appear in the middle of July. As an adult they have a black head and grayish wings with black spots when they are at rest, wings tucked in. The tips of the wings are a pattern of black rectangular blocks with grey outlines. When its wings are out the Spotted Lanternfly’s hind wings are red at the base and black at the tip with a white stripe dividing them. The red portion of the wing has black spots. The abdomen is bright to pale yellow with bands of black on the top and bottom surfaces.

If you see spotted lanternfly, report it! 1-866-253-7189; Badbug@pa.gov

damage in PA’s woods. The insect is originally from northeast Asia and was first found in Michigan in 2002. Since then it has spread into many states, including Pa, and has killed an estimated 50 million ash trees.

damage in PA’s woods. The insect is originally from northeast Asia and was first found in Michigan in 2002. Since then it has spread into many states, including Pa, and has killed an estimated 50 million ash trees. nditions Roy and the forester he was working with used mules and Belgium horses for the operation.

nditions Roy and the forester he was working with used mules and Belgium horses for the operation.

know what it looks like in each of those stages, you can help agricultural scientists who are working to prevent the spread and prevent further damage to Pennsylvania’s forests and farms.

know what it looks like in each of those stages, you can help agricultural scientists who are working to prevent the spread and prevent further damage to Pennsylvania’s forests and farms. The first stage begins emerging from the egg masses in mid-May. At this point it’s an instar (an immature stage of an insect) nymph. It’s black with white spots and no wings.

The first stage begins emerging from the egg masses in mid-May. At this point it’s an instar (an immature stage of an insect) nymph. It’s black with white spots and no wings. Adults look very different than the nymphs and start to appear in the middle of July. As an adult they have a black head and grayish wings with black spots when they are at rest, wings tucked in. The tips of the wings are a pattern of black rectangular blocks with grey outlines. When its wings are out the Spotted Lanternfly’s hind wings are red at the base and black at the tip with a white stripe dividing them. The red portion of the wing has black spots. The abdomen is bright to pale yellow with bands of black on the top and bottom surfaces.

Adults look very different than the nymphs and start to appear in the middle of July. As an adult they have a black head and grayish wings with black spots when they are at rest, wings tucked in. The tips of the wings are a pattern of black rectangular blocks with grey outlines. When its wings are out the Spotted Lanternfly’s hind wings are red at the base and black at the tip with a white stripe dividing them. The red portion of the wing has black spots. The abdomen is bright to pale yellow with bands of black on the top and bottom surfaces.