Sometimes you have to buy a property people think is already public and actually make it public.

Thanks to support from our members and extra help from George and Shirley Durrwachter that just happened. For years, people have used a property on the Avis side of the Route 150 bridge over Pine Creek to get on and off the Creek in kayaks, canoes, and tubes. They have fished here, swam here, and even sat in a chair while the Creek flowed over their feet and legs.

Everyone seems to think the Bureau of Forestry owns the property.

They don’t.

Well, not yet.

NPC bought the property Friday, June 28, 2019 and will be conveying it to the Bureau of Forestry in the next year, then it WILL be a public property, owned by the Bureau of Forestry and managed as part of the Tiadaghton State Forest.

The property was owned by an individual who had development plans for the property. However, when those plans fell through the owner looked to selling the property. When a local resident learned of the potential sale, he became concerned that the public might lose access to the Creek during the sale. This prompted him to reach out to the Tiadaghton State Forest District Forester.

The Bureau of Forestry started working with the landowner to buy the property. While the landowner was agreeable to selling the property, he couldn’t wait as long as the Bureau of Forestry would need for their acquisition process. As a state agency, when the Bureau buys a property there are a variety of other Departments that need to review documents and approve the transaction.

The Bureau of Forestry asked NPC to buy the property and then work through the Bureau’s process to sell the property to the Bureau.

George and Shirley Durrwacther donated the funds for the purchase price of the property. George grew up on Pine Creek. Fishing, swimming, and floating. He and Shirley recognize the recreational value the Creek provides for residents and visitors alike and wanted to help keep access in place for people to use and enjoy the Creek.

NPC’s members and donors provided other resources needed to get the project started. A sales agreement was drafted; the DEP files for Pine Creek Township, Clinton County were reviewed; and the title search started.

That title search found a 1947 deed that referenced a “frame gasoline station.”

Those three words carry a lot of weight with them. A geologist was hired to prepare a Phase I environmental review. His review was complete, but there weren’t any records showing storage tanks being removed from the property. Pennsylvania didn’t keep records on underground storage tanks until the 1980s.

The Clinton County Historical Society looked to see if the Sanborn maps for Avis or Jersey Shore showed the area. The Sanborn Map Company published very detailed maps for fire insurance companies through the 1970s. The maps detail the buildings in over 12,000 towns and cities in the United States. There wasn’t a Sanborn map that showed the area of this property.

Avis Canoe Launch parking area

Creek access in the wintertime

A group of “local guys” who meet for coffee a couple mornings a week were asked if they remembered anything about the property. They remembered the old ice plant, and the gas station up the road, but none of them remembered a gas station on this property. Although, they did appreciate being asked and having something new to talk about for a couple of days.

Without reports or documentation that the tanks were gone, additional steps were needed. Soil sampling and ground penetrating radar were done. The soil samples were all okay. NPC shared the report with two geologists who read the report and agreed it looked good.

The ground penetrating radar was the next step. It was a much shorter process than the soil sampling. When he was done and packing up his equipment Josh, the technician who did the ground penetrating radar said, “There are no big metal things underground.” The official report was longer, but had the same message.

With those steps complete, a closing could be scheduled. The documents were signed without a hitch. Staff are working to get signs made with the property’s 911 address and have reached out to local emergency services to determine who needs keys to the existing gate on the property.

Now the process of selling the property to the Bureau of Forestry can begin. Documents are being drafted and reviewed. Reports are being shared and updated. Keep an eye out in future newsletters for more information about the project and updates on when it will become part of the Tiadaghton State Forest.

You can help work on projects to create more access to creeks and streams and rivers for fishing, paddling and splashing. You can create more access to trails for walking and birding and biking and skiing.

You can help work on projects to create more access to creeks and streams and rivers for fishing, paddling and splashing. You can create more access to trails for walking and birding and biking and skiing.  “March Madness” may refer to college basketball playoffs, but at NPC it’s Macro Madness.

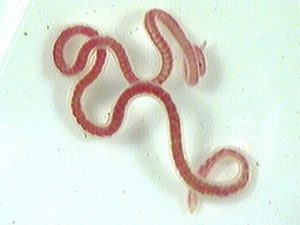

“March Madness” may refer to college basketball playoffs, but at NPC it’s Macro Madness. These worms are pollution tolerant, meaning they can live in polluted water. Their body is soft, cylindrical, and long – like the earthworms you find in your yard or on pavement after a summer rainstorm. The body is divided into many segments (usually 40-200).

These worms are pollution tolerant, meaning they can live in polluted water. Their body is soft, cylindrical, and long – like the earthworms you find in your yard or on pavement after a summer rainstorm. The body is divided into many segments (usually 40-200). Midge Larvae are another pollution tolerant species. Midges are small insects that look like mosquitoes, but don’t bite. Midges, like a lot of insects, go through various life stages.

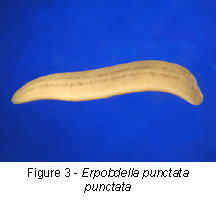

Midge Larvae are another pollution tolerant species. Midges are small insects that look like mosquitoes, but don’t bite. Midges, like a lot of insects, go through various life stages. Leeches can live in polluted water. They are considered a pollution tolerant taxa.

Leeches can live in polluted water. They are considered a pollution tolerant taxa.