By Susan Sprout

What a joy to get outside and see what is happening, after being cooped up for days by rain showers! I am not complaining because we do need the rain to recharge above-ground and underground water resources. I would like to share some of the things we saw during our lovely time outside.

The rain must have really been pelting down to clear out a ditch on the road’s edge and reveal what appeared to be fresh wave-like mud bumps alongside it. Wow! On closer inspection, those riffle marks I photographed were not laid down recently. They are ancient rock-hard shale built up over millions of years and lifted high by collisions of the continental plates to create our endless mountains.

We saw hordes of fresh orange daylilies blooming everywhere. They will continue to provide us with new flowers until all their buds are used up. Here today, mostly gone tomorrow – droopy heads shriveled up and falling off.

Aaaah! It was definitely “Spa Day” for the Green Frog we carefully passed. The spa puddle took up most of the road, but he or she did not flinch a bit as the waves of our passing went by. It was a good, wet day in the neighborhood there! The green upper lip, the large eardrum, and the prominent ridges on the side of its back give hints of the species even though it stayed submerged.

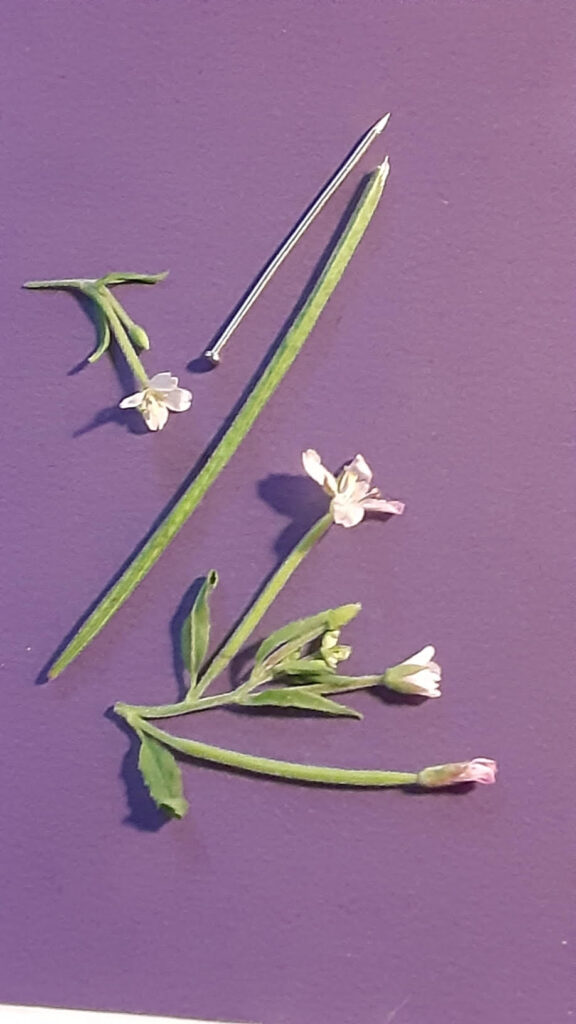

Deptford Pinks, small, pinkish-purple flowers with skinny leaves lent a bit of color to the fresh green of happily watered plants. This flower may have originally been found growing in Deptford, SE London! It has since been extirpated in England.

Cattails in a roadside ditch! I like seeing them all dressed out with both types of flowers showing. The top, staminate ones, provide the pollen for the lower pistillate ones that will make the seeds – lots of seeds. I bet you have seen them as they ”fluffed out” during the fall and wintertime, sending their seeds in furry bunches to waiting wet areas.