The Northcentral Stream Partnership efforts to decrease erosion and improve aquatic habitat in the Little Shamokin Creek Watershed began in 2009, starting with in-stream restoration projects at just two sites. Over the past decade, they have completed projects at 15+ sites in the watershed and are seeing some of the long term, positive changes from the fruits of their labor!

Get to know the Little Shamokin Creek Watershed:

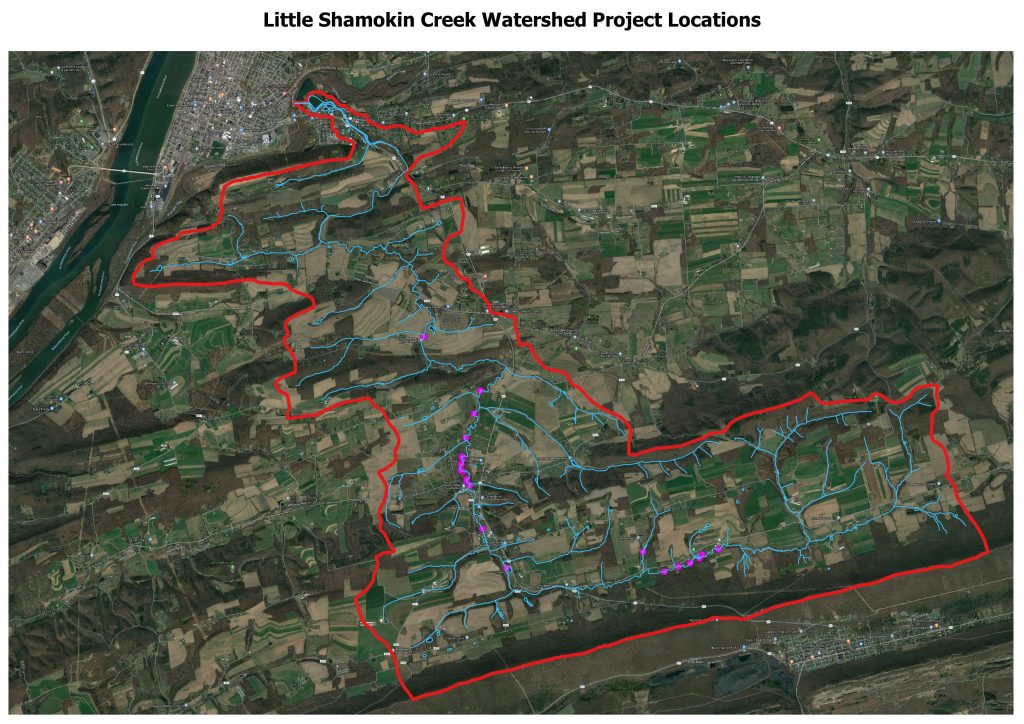

The Little Shamokin Creek Watershed (LSCW) covers approximately 37 square miles and is a sub watershed of Shamokin Creek, originating in Northumberland County to include four municipalities (Rockefeller, Shamokin, Upper and Lower Augusta townships). It is designated for protection of Cold Water Fishes (CWF). The LSCW is largely forested, 65%, with tree farms and deciduous stands. Agricultural areas of mostly pastures and croplands make up an additional 30% of the watershed & urban/developed lands, 2%. (www.littleshamokincreek-watershed.org).

A Before & After at project sites in the watershed:

Eroding and undercut stream banks, poor bank vegetation, poor riffle habitat, and embedded substrate are all visible signs of an agriculturally impaired stream. The Partnership’s use of in-stream stabilization structures and implementation of Agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs), along with continued support from the Little Shamokin Creek Watershed Association (LSCWA) and the Northumberland County Conservation District, are steadily helping to bring the watershed back to health.

Signs of Success:

The Partnership has worked in collaboration with various educational institutions over the years to help document the pre and post-construction conditions of the streams. Data collected by the Freshwater Research Institute at Susquehanna University* shows an increase of lithophilic fish and macroinvertebrates in the watershed.

Let’s Talk Lithophilic Fish

Lithophilic fish are species of fish that use the gravel bottoms in streams to spawn. Typically, the fish are laying their egg on the stream bottom and need to attach the eggs to rocks, or use the spaces between rocks to hide their eggs.

If the stream bottom is covered in silt and sediment, lithophilic fish may not reproduce at all, or reproduce in much smaller numbers. The sediment coating the rocky bottom may prevent eggs from “sticking” to the rocks and if the spaces between rocks are filled with sediment there may not be any place for the eggs, or the spaces may be smaller.

The in-stream structures the Partnership uses to stabilize streambanks also help to increase the speed of the water flow during normal conditions. These water flows are not necessarily “fast,” but there is movement in the water. That movement helps keep sediment from settling out onto the stream bottom and can help move sediment that is laying on the stream bottom.

Multi-log vanes and single-log vanes are variations of the same structure. The purpose is to remove pressure from the banks of the stream, and trap sediment along the bank to help restore the banks that were eroded. Typically, the Partners will install a series of these structures. As one structure helps add a little more speed to the water flow, the next structure downstream will trap the sediment from above while also helping to keep the water moving.

Making Sense of Macros

To collect data on the macroinvertebrates present, the scientists use a net with an opening shaped like a capital letter “D.” They shuffle their feet and stir up the bottom of the stream for a certain period of time and certain area. They then use the net, flat side down, to collect all the material that is dislodged from their kicking and shuffling. The material in the net is then transferred to labeled buckets. Formaldehyde is added to the contents to preserve the material. The lid is snapped on and the sample is taken back to the lab for processing.

Back at the lab, the material is dumped into a tray, and a random section of the tray is isolated. This isolated section is then moved to another tray. The scientist then carefully and methodically pulls out the macroinvertebrates (water bugs and water worms). Once they are confident they have pulled everything out of the sample, they identify the species of macroinvertebrates found and tally how many of each species were in the sample. This information is then used to determine how clean or how polluted the water is.

Like Lithophilic fish, macroinvertebrates use the stones and spaces between them on stream bottoms. You will find macroinvertebrates living in those gaps or building “homes” directly on rocks. Another way the log structures help macroinvertebrates is by providing woody material the stream. Macroinvertebrates eat wood and leaves. If there’s not wood and leaves in the stream, you’re not going to have the macroinvertebrates that live in clean water and feed fish that live in clean water.

Many of the project sites the Stream Partnership has worked at there aren’t trees along the stream. We’re working in an open pasture or cropland. This means there will not be a lot of leaves, twigs, or tree branches falling into these streams providing food for the macroinvertebrates. One of the functions trees along a stream will provide is that “food” for macros, which then become food for fish. The property owned by Little Shamokin Creek Watershed Association is mostly wooded. The trees are larger and extend out over the stream far enough that they’re shading the stream in the summer (trout like cooler water) and the leaves and twigs can fall into the stream providing food.

*Source: Unpublished data by Dr. Jon Niles and Mike Bilger, Freshwater Research Institute, Susquehanna University.

Clean Water = Healthy Communities

It sounds simple. As a basic human need, protecting and cleaning up our local water sources should be a priority for every community. Beyond being able to turn on your tap and know that you can get a glass of pure, clean water; a healthy watershed provides opportunities to fish, swim, and other forms of recreation and can be a catalyst for the local economy. From fishing derbies to farmlands, your watershed is vital for your quality of life and your community. Seen below is a father-daughter duo standing on a multi-log vane at LSCWA youth fishing derby – an annual event made possible through the ongoing efforts of LSCWA, the Partnership, and other conservation groups to clean-up the watershed.

While the research discussed above shows the data supporting the recovery of the watershed, another quick way to assess a stream’s health is to ask an angler! Matt Miller, a Northumberland County native and current Director of Science Communications for the The Nature Conservancy, returned to the area to fish Little Shamokin Creek. He shares about this positive experience in his first novel, Fishing through the Apocalypse. You can meet Matt at a book-signing event being held at the Little Shamokin Creek Watershed Association’s pavilion on Monday, September 30 at 6:30pm.

Leading by Example

At the heart of the Northcentral Stream Partnership, are the dynamic people and organizations that have helped grow the programs impact. As the Partnership evolved and maximized its efforts over the years, so too did the individuals involved. Interns became professionals. Landowners became stewards. Volunteers became advocates.

Now the Partnership has become a model for broader reaching plans to help improve water quality across the state and the entire Chesapeake Bay watershed. As a member of NPC or a partner, such as the Little Shamokin Creek Watershed Association, we hope you are as proud as we are to be a part of the solution to restore the health of Pennsylvania’s waterways. Cheers to another 10 years!